What the Old Timetables Tell Us

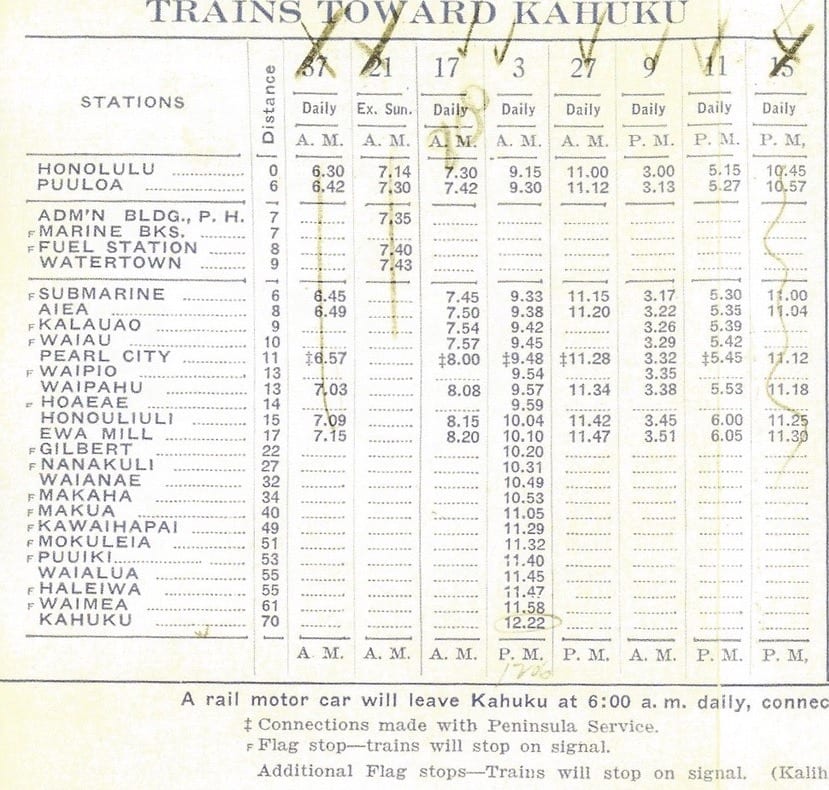

Heading from Iwilei to Aiea in 1921? Just move your finger across and determine your choices of train to take-what time of day what class car. Most people use a timetable in just that way-as a throwaway sheet to help them plan an outing or figure what train they need

Luckily, not all timetables were thrown away, as to the discerning railfan, they are an object worthy of study and are able to unlock many otherwise hidden facts. The timetables issued over the years by the OR&L contain a wealth of direct information, and much can be inferred from them as well. This is particularly true of employee timetables, which include freight train schedules and the railway’s operating rules, called “Special Instructions.’

Early timetables reflect the gradual growth of the line. They also reflect the initial alignment of the main line through Kalihi out to the Damon estate at Moanalua and Pu’uloa.

Near the main depot at Iwilei, the harbor was dredged and the fishponds filled in by Dillingham Construction, thus creating both a complex of docks and new acres of dry land where industries served by the railroad could locate. The pineapple canneries, originally built near the fields around Wahiawa, were soon moved down to OR&L’S fill land in Iwilei, as it was far easier to bring the fruit to the labor pool than vice-versa.

The new main line on the causeway across Kalihi Kai basin to Pualoa became increasingly important. By 1903 passenger trains, at least, ceased to be routed on the old Kalihi main line, and it was eventually abandoned.

The timetables also reflect the construction of the Wahiawa Branch in 1906 which almost immediately carried scheduled passenger traffic, in addition to the pineapple transport which was its impetus.

The table on the next two pages shows a variety of information about the railroad across the decades as reflected in the timetables, including the rise and fall (and rise again just before and during the war) of passenger traffic, reflected in the number of trains per day. Note that extra trains to handle overflow were often added to the day’s schedule-especially during the war, and that these do not appear on the timetables.

Same for freights. The timetable show scheduled fright trains over the years, but these were augmented by unscheduled extras and work trains, as well as specials like the Yokohama garbage trains. These last were originally instituted just before the war when the incenerator in Honolulu broke down. They continued run trash to Yokohama after the attack on Pearl Harbor to avoid the possibility that the incinerator’s flames might guide in enemy bombers.

By all indications, passenger traffic peaked in the early 1920s, then declined as buses and especially autos and trucks trucks during World War II as defense workers and military personnel piled onto the trains, when gas rationing discouraged the use of automobiles.

The timetables also tell us about the operations of several connectors for passenger traffic. For several years, Fort Kamehamea on the south side of the entrance to Pearl Harbor, was a destination in itself for passenger trains from Honolulu.

By the same token Dillingham developed property on the Pearl Peninsula and provided service to the Pearl City station for many years. Late in the line’s operations passenger traffic to Wahiawa was more frequent than that around the leeward coast to Hale’ and Kahuku, but a connecting shuttle was instituted from the Ewa Mill town to Waipahu to meet the Wahiawa trains.

Many newspaper train schedules appear in Chapters 1 and 2, and on the pages following the chart are sample timetables from the 1921 heyday of the OR&LS operations, a combination Train & Bus trip around O’ahu and “Special Instructions” for train crews, both dated 1930.